- Home

- Paige Britt

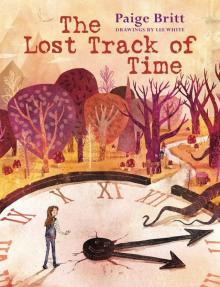

The Lost Track of Time

The Lost Track of Time Read online

The

Lost Track of

Time

Paige Britt

DRAWINGS BY LEE WHITE

Due time

All the time

The

Lost

Track

of

Time

The

Lost

BY Paige Britt

DRAWINGS BY LEE WHITE

SCHOLASTIC PRESS

NEW YORK

Track of

Time

Text copyright © 2015 by Paige Britt

Illustrations copyright © 2015 by Lee White

All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Press, an imprint of

Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. SCHOLASTIC, SCHOLASTIC PRESS,

and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of

Scholastic Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled,

reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval

system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or

hereafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher. For

information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions

Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Britt, Paige, author.

The lost track of time / by Paige Britt; drawings by Lee White.

— First edition. pages cm

Summary: Penelope is an imaginative girl, whose every day has been rigidly scheduled

by her mother— until one day she falls through a hole in her calendar and lands in the

Realm of Possibility, where she discovers that it, too, is stuck in a track of time, and

only she can save it.

1. Time— Juvenile fiction. 2. Imagination —Juvenile fiction.

3. Self-actualization (Psychology)—Juvenile fiction.

4. Mothers and daughters —Juvenile fiction.

[1. Time—Fiction. 2. Imagination—Fiction.

3. Self-actualization (Psychology) —Fiction.

4. Mothers and daughters —Fiction.]

I. White, Lee, 1970− illustrator. II. Title.

PZ7.B78065Los 2015 [Fic]—dc23 2014012529

e-ISBN 978-0-545-53814-5

First edition, April 2015

chapter one

Beep. Beep. Beep. Beep.

Penelope dragged one eye open and then the other. She’d been dreaming

about a fire-eating lizard that spoke in riddles. The lizard was right in the

middle of telling her something important when the alarm went off. She glared

at the clock. It glared back: 6:00 a.m.

Here it was, the first day of summer vacation, and even now her mother

expected her to get up and get busy. Penelope shut off the beeping and sat up. She

dangled her feet over the bed and stared down at her toes. She had to be show-

ered, dressed, and ready for breakfast in 30 minutes, which meant she’d better

hurry. She wondered what it would be like to have a day off. Just once.

This won’t take long, she told herself. Penelope dropped to the floor and began

rummaging underneath her bed for one of the notebooks she kept hidden there.

Penelope’s room was extremely neat. Her mother was fond of saying, “A

place for everything and everything in its place.” That’s why Penelope kept

everything that had no place in her room underneath the bed. There was the

hamster habitat she was building (Penelope didn’t own a hamster), the diary she

was writing for her twin sister lost at sea (Penelope was an only child), and

the invisible ink kit for sending secret messages (just in case she ever got

stuck in a Turkish prison). And of course, there were the notebooks. Piles of

notebooks filled with all the fascinating words she had collected over the years

and all the stories she had written with them.

Penelope pushed aside a box of hamster food and pulled out a small red

notebook. She flipped it open and used the pencil tucked between its pages to

make a quick sketch of the lizard from her dream — big eyes, long body, and a

curling tongue, licking up bits of flame. When she finished, she sat back and

tried to think of a name for the creature. It wasn’t like naming a dog or a cat. It

had to be unusual, like Beauregard or Eckbert. No. Too complicated. She

needed something simple like . . . Zak. That was it!

Now that she had a name, what next? Zak couldn’t just eat fire and speak in

riddles. He needed an adventure. Penelope chewed on her pencil to help her think.

The smell of bacon drifted up from the kitchen and her stomach growled. She

chewed harder. Maybe Zak belonged to a circus made up entirely of reptiles . . . or

maybe he lived in a volcano that was about to blow up the world . . . or . . .

Bacon!

Penelope dropped her pencil. She realized what the smell meant. She was

late. Her mother had started making breakfast, and Penelope was expected at the

table. She shoved her notebook back under the bed, tore off her pajamas, and

threw on some clothes. She raced down the stairs, combing her hair with her

fingers. As soon as she stepped into the kitchen, her mother gave her “the look.”

“Do you know what time it is?”

Penelope slid into her chair. “I know,” she mumbled. Penelope couldn’t

tell the truth — that she’d lost track of time. Her mother wouldn’t understand.

Not when there was a clock in every room of the house and a watch on her

wrist. Just because Penelope wore a watch, though, didn’t mean she looked at

it. It made her nervous. The second hand never sat still. It swung around and

around, sweeping the day away like sand.

Penelope’s mother put breakfast on the table and sat down. “Your father

will be back from his run any minute now, so we’d better get started.” She

reached across the table for her leather three-ring binder. “Let’s see what’s on

the schedule for today, shall we?”

Here we go, thought Penelope, slumping over her plate.

“Sit up straight,” said her mother without looking up.

Penelope felt a knot form in her stomach as she waited for her mother to

begin. The binder held a calendar that served as Penelope’s schedule. Each page

was a single day and each day was filled with a long list of things she was expected

to do. Penelope’s mother ripped yesterday’s page off the calendar and let out a

satisfied sigh. “Looks like you’ve got a full day ahead of you.” She held out the

calendar for Penelope to see.

There was the month (May), the date (29), and the quote from Poor

Richard (whoever he was). After that, lines and lines of her mother’s neat

handwriting filled the page:

May 29

Be always ashamed to catch thyself idle.

6:30–7:00 Breakfast

7:00–7:30 Daily chores

7:30–8:30 Piano practice

8:30–8:45 Free time

8:45–9:15 Drive to dentist

9:15– 10:15 Dentist appt.

10:15–10:45 Drive home from dentist

10:45–11:45 SAT vocabulary drills

11:45–12:15 Wash and polish bike

12:15–12:30 Ride bike

12:30–1:00 Lunch

1:00–2:00 Math tutoring

2:00–3:00 Write b-day thank-you cards NEATLY!

3:00–4:30 Get started on summer reading list

4:30–5:30 Cooking lesson

5:30–6:30 Dinner

6:30–6:45 Free time

6:45–7:00 Call Grandma

7:00–8:00 Tidy room and get ready for bed

Penelope’s mother cleared her throat and began to read off all the

day’s activities. As she did, Penelope wondered for the hundredth time

just who Poor Richard was. Even though she had never met him, she didn’t

like him. He was always saying things about “industry” or “sloth.” What

exactly was sloth? It seemed like it had something to do with being lazy.

But then again, wasn’t a sloth an animal that looked like a sock puppet?

Maybe a sloth would make a good sidekick for Zak, the fire-eating

lizard . . .

“Penelope!”

Penelope looked up. Her mother was staring at her expectantly. “I said,

hurry and finish your breakfast. It’s almost time for your daily chores.”

Just then, the front door swung open and a voice called out,

“I’m home!” A minute later her father bounded into the kitchen.

“Hi, pumpkin,” he said and rumpled Penelope’s

hair. “It’s another beautiful day out there.” He pronounced

the word beautiful as if it were three words — beau-ti-ful.

“How did it go, dear?” asked her mother, flipping to

the back of the binder where she kept an account of his

daily runs — time, date, distance.

“Great! Five miles, 41:4.”

Penelope’s mother recorded the information and shut

the binder. “Your day is off to a good start,” she said, as if the

numbers proved it.

“It certainly is!” Her father downed a glass of water and

then sat at the table to peel a banana. “I bet you have a lot

to look forward to today, huh, kiddo?” he said and reached

for the paper.

Penelope crammed a piece of toast in her mouth

and mumbled something unintelligible. Her dad wouldn’t

understand. He looked forward to every day. He was an insurance agent, and

although he helped people prepare for disasters — death, disease, fire — he

was so happy all the time you would have thought he worked at Disneyland.

Penelope finished her toast and got up from the table.

“I guess I’d better get started on my chores.”

Her dad glanced up from the sports page. “Go get ’em,

tiger,” he said, giving her a thumbs-up.

Her mother, who was on the

phone, just waved.

Monday was Penelope’s day to vacuum the living and dining room floors.

As she walked back and forth, vacuuming in neat lines, she thought about the

other kids in her class. They probably had summers filled with nothing but

hanging out at the pool all day and going to slumber parties at night. Penelope

had never been to a slumber party in her life. “Early to bed, early to rise,” was

another one of Poor Richard’s rules.

Penelope changed the vacuum attachment and began sucking up the dirt

and crumbs between the couch cushions. She knew it was no use complaining

about her schedule. No matter how packed it was, her mother’s was even worse.

Penelope’s mother was an event planner. She planned parties, business meet-

ings, weddings, bar mitzvahs, and anything else that needed to go perfectly.

From what Penelope could tell, her mother spent all her time on the phone or

the computer organizing other people’s lives. Apparently no one minded,

because they gave her money to do it.

Penelope knew she should feel lucky to get her mother’s help for free, but

she didn’t. Her mother said that following a daily schedule was the best way to

prepare for the future. Penelope didn’t know how she could prepare for some-

thing that was so impossible to imagine. She could hardly picture herself

graduating from middle school, much less going to college. Besides, the only

thing she wanted to do was be a writer. Last year her English teacher,

Mr. Gomez, had given her a magazine full of stories written by kids her age.

“Keep reading and keep writing,” he had told her. “And when you’re ready, you

should send this magazine one of your stories. I think you have a real chance of

getting published.” She couldn’t get his words out of her mind.

Penelope finished vacuuming the living room and moved on to the dining

room. The only other person who encouraged Penelope to write was her neigh-

bor, Miss Maddie. When Penelope was little, before she started school, her

mother would drop her off at Miss Maddie’s house whenever she had a business

meeting to attend or an errand to run. Once in a while, Penelope spent the

whole day at Miss Maddie’s house. Even though it was just down the street, it

felt like a different world. At Miss Maddie’s house, Penelope was allowed to do

what her mother would call “nothing.” It wasn’t the nothing where you watched

TV for hours, waiting for the day to pass. This nothing was more like a blank

page Penelope could fill however she wanted.

Whenever Penelope stayed with Miss Maddie, she would spend all her

time reading, writing, or just staring out the window. Miss Maddie didn’t

mind; in fact, she often joined in. Once they had spent an entire afternoon look-

ing for faces in the wood grain of Miss Maddie’s dining room table. After they

found a face, they drew it on a piece of paper and gave it a name like “Ichabod”

or “Millicent.” Next they made up elaborate stories about the characters, which

Penelope wrote down in a notebook. Whenever Penelope asked if they

were wasting time, Miss Maddie would just roll her eyes and say, “Don’t you

worry about the time, it’ll keep track of itself.”

Penelope wished she believed that.

The grandfather clock chimed 7:30 a.m. and Penelope turned off

the vacuum cleaner. “Time for piano practice!” her mother called from the

other room.

“I know, I know!” Penelope called back.

She put away the machine as fast as she could and ran down the hall to the

living room. She had exactly one hour to complete her sight-reading and theory

exercises, practice her scales, and play through all the music assigned by her

piano teacher. If she finished by 8:30, she could use her free time to visit with

Miss Maddie.

Penelope rushed through her scales and then played all her practice pieces.

The piano theory and sight-reading worksheets took longer to complete, and

by the time she finished, her hour was almost up. She slammed her workbook

closed and headed for the back door. “I’m going to Miss Maddie’s,” she called

over her shoulder.

“Be back in fifteen minutes!” her mother shouted after her. “We leave for

the dentist at 8:45 sharp!”

Penelope could almost feel the seconds ticking away as she ran down the

street toward Miss Maddie’s ho

use. Miss Maddie had lived at the end of Ginger

Lane even before there wasa Ginger Lane or any such thing as the Spicewood

Estates housing development. She had once shown Penelope a faded black-and-

white picture of her house surrounded by a wide-open field and tall oak trees.

Instead of Ginger Lane, a long dirt road ran up to the front gate.

“Once they sold this land and began building Spicewood Estates, houses

sprouted up overnight,” Miss Maddie had said.

As she ran, Penelope imagined she was racing through a field with

houses popping up out of the ground, each with a door, two windows, and

a driveway.

Miss Maddie’s house wasn’t like anyone else’s house. It didn’t have a mail-

box perched on the corner of a neat lawn and a walkway dotted with flowers.

Instead, it had an old paint-chipped fence covered with ivy. The front yard had

a patch of sunflowers, an overgrown herb garden, and an enormous oak tree.

The oak tree spread out across the yard, with branches that almost touched the

ground. A pathway ran through the front gate, around the tree, and stopped at

a bright purple door.

No one in all of Spicewood Estates had a purple door.

No one except Miss Maddie.

Penelope opened the gate and hurried up the path. She would have

preferred to take her time. Sometimes she found stray items along the

way — glossy wrappers, colored string, or small toys. Miss Maddie told her

that birds would often spot shiny objects on the ground and use them in their

nests. Penelope suspected that the little treasures she found were gifts from

Miss Maddie meant for the birds.

Today, however, Penelope didn’t have time to scavenge for shiny objects.

She rushed up to the door and used their secret knock.

Knock-knock-knock. Knock. Knock.

Miss Maddie flung open the door. “What a nice surprise!”

“I’ve only . . . got . . . a minute,” said Penelope, trying to catch her breath.

“Nonsense,” said Miss Maddie. “You’ve got all the time in the world.”

The Lost Track of Time

The Lost Track of Time