- Home

- Paige Britt

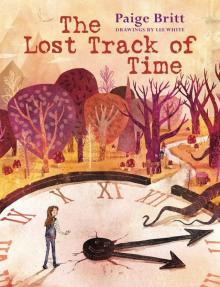

The Lost Track of Time Page 9

The Lost Track of Time Read online

Page 9

Dill wasn’t stiff as a board. He was bored stiff! And the tears? Bored to

tears. Soon he would be bored to death.

“Stop! Please stop!” Penelope pleaded with the Wild Bore. He never even

blinked. His eyes were locked on Dill. Penelope didn’t exist.

By now the Bore looked radiant. His once-gray hair was rich as

midnight, and his gray eyes flashed every color in the rainbow — red, green,

yellow, blue — a new color every few seconds. Dill, on the other hand, was

white as chalk. Penelope grabbed his wrist, searching for a pulse. She couldn’t

feel anything!

Penelope was so desperate she flung herself at the Bore, kicking and

screaming. “Ayyyyyyy!”

The Bore fought back. “Run along, child. The grown-ups are busy!” His

chatty, conversational tone was now a vicious snarl. He grabbed Penelope’s arm

and shoved her to the ground with a thud.

When Penelope fell, she landed on something stiff and lumpy. Her note-

book! She sprang to her feet and snatched it from her pocket. Dill had said the

only way to stop the Bore was to get a word in edgewise. That was exactly what

she would do!

Penelope took out her pen and tore a piece of paper from her notebook.

She would fight fire with fire. She would outwit the Wild Bore with words. But

not just any words. Interesting words! The Bore might have shut her up, but she

knew more than one way to be heard.

Penelope quickly wrote down the most interesting word she had

ever seen. This was the bait. Then, on nine separate scraps of paper, she wrote

nine more fascinating words. She didn’t know what they all meant, but that

didn’t matter. In fact, that made them all the more fascinating. She stood

on the tips of her toes and held up the most interesting word in the world

for Dill to see:

Taj Mahal

“Stop that this instant!” squealed the Bore, pushing Penelope aside. But it

was too late. Penelope had gotten a word in edgewise. Dill turned his head ever

so slightly toward Penelope. Quick! She held up the next few words.

First

Ambrosia, quickly followed by Nova.

That did the trick. A blush of color came into Dill’s face and slowly he

began to move his head away from the Bore and toward Penelope.

Penelope backed away, holding up one word and then the next:

Kumquat . . .

Cowpoke . . .

Conundrum . . .

Dill inched toward Penelope, his eyes locked on the tempting words. The

Bore grabbed desperately at Dill, pleading, “Listen to me! Me! Meeee!”

Nebula, Doodle, Blurb.

The words were coming faster now and Dill walked with purpose

after them. The color was rushing to his face and his red hair was ablaze!

The Bore was almost out of earshot when Penelope silenced him with her final,

fascinating word:

Skedaddle!

“That was a close call,” said Penelope after the Wild Bore was safely behind them.

“Not at all!” countered Dill. He was walking briskly down the trail,

swinging his arms and taking deep breaths. “As soon as I realized the Bore was

ignoring you, I knew we’d be okay.”

“You did?”

“Of course! You were a tremendous threat, but the Bore didn’t seem to

notice.”

She was a tremendous threat? Penelope mulled this information over. It

hardly seemed possible. She rarely had the upper hand in anything!

“From what I can tell,” continued Dill, “the Wild Bore didn’t think you

were the least bit interesting, which means he didn’t think you were very

dangerous. You and I both know that’s bunk. Rubbish. Total nonsense! Young

people are the most interesting people around. But Wild Bores wouldn’t know

that. And do you know why?”

“No,” said Penelope.

“Because they were never children! Of course, at one time they looked like

children and could easily be mistaken for children, but they were really Little

Knowitalls, which is a different thing altogether.” Dill glanced over at her.

“Certainly you’ve met a Little Knowitall?”

chapter ten

Penelope thought about the girl with pigtails from science camp. “Oh,

yes,” she said. “Lots of them.”

“Well, then you know exactly what I’m talking about.”

By now they had reached the row of trees where they were headed. Just as

Dill had said, a creek wound its way through the tree roots. Dill found a shallow

area scattered with rocks and leapt lightly from one to the next, chattering all

the while. “Almost all Little Knowitalls become Wild Bores. Although now that

I think about it, a few do manage to avoid that fate by learning to be inquisitive

about something besides themselves.” Dill reached the other side and turned

back to look at Penelope. “Speaking of being inquisitive . . . how do you know

all those fascinating words?”

“Oh, well, I don’t know them all,” Penelope explained, balancing her foot

on a rock. “But I guess you can say I collect them.” She raced across the creek and

landed on the other side with a hop. “I never expected them to come in handy.”

“Handy?” exclaimed Dill. “They were critical. Vital. Absolutely essential.

I wouldn’t have survived without them!”

Penelope beamed. She wasn’t used to her words being important.

“I suggest you expand your collection immediately!” said Dill.

Penelope’s smile faded. She thought about her notebooks filled with draw-

ings and sketches, dreams and ideas. Ideas that would turn into stories if only she

could get them flowing again. “I’m not sure there’s any use,” she mumbled.

Dill’s eyes grew large. Huge, actually. For once, he didn’t say anything.

He just stared at Penelope, waiting for her to continue.

But she didn’t want to continue. She didn’t want to tell Dill the awful

truth. It was no use collecting words because she would never use them. She

would never be a writer, not if she couldn’t moodle. Dill had said it

himself — she was an anomaly. A failure.

Penelope stole a glance up at Dill. He was waiting patiently for her to

speak. “I want to be a writer,” she said, her voice still soft. “And I used to believe

that one day I could be, even though my parents didn’t think so. I was full of

story ideas — so full I couldn’t keep track of them all. But out of the blue

they . . . they disappeared.”

Dill took a step back.

“That’s why I wanted to find the Great Moodler,” Penelope rushed on. “I

thought she could help me find out where all my ideas went, help me become a

moodler again. If I can’t moodle, I can’t write.”

“That,” said Dill, pointing straight at her, “is a brilliant plan. You find the

Great Moodler and get all your ideas back. And then the Great Moodler can find

my lost way and I’ll be an explorer again!”

This time it was Penelope’s turn to take a step back. She hadn’t expected

Dill to actually adopt the plan. “But I’ve run out of ideas and can’t moodle up any

new ones. I’m not sure how to find her without . . .”

“You can do it,” said Dill, cutting her off. “Look how

you handled that

Wild Bore!” He turned and began to climb up the creek bank. “You’re young

and inquisitive, a moodler and a word collector,” he called out, listing her

qualifications. “What more do you need?”

A lot! thought Penelope. Those traits hadn’t led to much success in life

so far. Besides, had Dill forgotten about her attempt to use the moodle hat? She

had come up with nothing! Penelope was just about to remind Dill of this fact

when he let out a sharp cry.

“It’s gone!”

Penelope scrambled up the creek bank to join him. Standing atop it, she

looked out on a vast plain of rocks and boulders. “What’s gone?” she asked.

“The Range of Possibilities,” wailed Dill, pointing off into the distance. “It

used to be over there, along the horizon, and now it’s gone!” He began to pace

back and forth, wringing his hands. “You see what I mean? I can’t find anything

anymore, not even a mountain range. This is bad. Horrible. Completely

horrendous!”

Penelope stared at the plain. It was empty of any scenery except for rocks.

Miles and miles of rocks. It looked like it would be hard to cross. “What are we

going to do now?” she asked.

“We’ll just have to follow a hunch,” said Dill. He stopped pacing and

began to pat his pockets. “Do you have one? I seem to be all out.”

“Me?” asked Penelope. “Why would I have a hunch? I have no idea where

we are, much less where we should go.”

“Hunches aren’t ideas. They’re inklings,” explained Dill.

“Don’t inklings just pop into your head?”

“Exactly. And they pop out just as quickly. That’s why you’ve got to

catch them when you can. Push everything out of your mind and see what

pops out when you do. More than likely you’ll see a hunch. That’s when you

snag it!”

“With your hands?”

Dill looked at her as if she’d just said the moon was made of cheese. “Of

course not. By listening to it! But be sure not to think while you do it,” he

instructed. “Thoughts scare them away. Now then, clear your mind and then

look around a bit. You look up, and I’ll look down.”

Penelope couldn’t imagine what she was looking for, but she did as she was

told. She cleared her mind and then followed Dill’s lead. He was walking in

circles with his hands clasped behind his back, looking at the ground. Penelope

did the same, but looked up at the clouds.

Walking around and around, staring at the sky, made Penelope woozy.

Being woozy kept her from thinking too much, which turned out to be a good

thing. After walking for a few moments it dawned on her that she might feel less

woozy if she stopped walking and focused on one specific spot. With her neck

bent back, she locked her eyes on the spot above her nose. When her eyes

focused, she saw the most unusual thing. There, on the tip of her nose, sat a

small creature, so slight it seemed to be made of air.

Penelope froze, her eyes fixed on the tiny thing. “Dill!” she called in her

very quietest whisper. “Dill, come here.”

Dill rushed over. “Good job!” he said, slapping Penelope on the back.

Penelope stayed frozen in position. “Now what do I do?” she asked, hardly

daring to move her mouth.

“Just relax and concentrate on the question: What do we do now?”

Penelope gently returned her head to an upright position. She crossed

her eyes to check on the hunch. It was still there, resting on her nose.

“Hurry up,” said Dill. “We don’t want to wear the poor thing out.”

Penelope looked around, searching for some sign or clue that would tell

her what to do next.

“Don’t try to figure it out,” said Dill. “Just listen to your hunch.”

“But I don’t hear anything,” said Penelope.

“You’ve got to really listen,” urged Dill.

Penelope stopped looking around and relaxed. When she did, she heard a

small voice coming from what sounded like inside her own head. “Look up,” it

said. Penelope immediately checked to see if the creature was still on her nose.

It had disappeared. Oh, well, she thought, here goes.

She looked up.

There, along the far horizon, was a black speck moving quickly toward

her. It grew larger every second. Dill noticed it, too, and stood still, watching

it come closer. The speck was beginning to take shape. It looked like a bird — a

gigantic bird — a bird the size of a small airplane.

“RUUUN!” Dill shouted and, clutching his head, darted this way and that,

forward and back, dodging left, then right. Penelope didn’t move. Something

told her — was it a hunch? — she should stay right where she was. In seconds

the bird was upon them. Dill froze in fear and then dove for cover behind a

particularly large rock.

The bird circled around them a few times before touching down in

a storm of dust. Once the air cleared, Penelope got a better look. It was a bright

yellow bird with a long flourish for a tail. Black and gray bands striped its wings

and an elaborate looping plume swayed on its forehead. Its beak was brilliant

green and would have been beautiful if it didn’t look so sharp.

“Coo-Coo,” called the bird.

Its voice was loud, but so lyrical that Penelope relaxed. Something so lovely

wouldn’t eat a person, she reassured herself.

The bird made a deep bowing motion, one wing outstretched and the

other bent in toward its chest. “Coo-Coo, Coo-Coo!” This time it called out with

more insistence.

“I think it’s trying to tell us something,” whispered Dill from behind

the rock.

“I think you’re right,” agreed Penelope. “I’ll try to talk back.” Mustering

her courage, she addressed the gigantic bird. “Coo-coo, coo-coo,” said Penelope

in her best birdcall.

The bird cocked its head and half sang, half spoke, “How could . . . you-

you . . . be Coo-Coo?”

“Oh, but I’m not,” stammered Penelope. “I was just . . . I didn’t expect . . .

I mean . . .”

“And your friend?” said the bird, jumping onto the rock Dill was hiding

behind and peering down at him with interest. “Is he Coo-Coo . . . too-too?”

“Certainly not!” said Dill, embarrassed at being caught hiding. He jumped

to his feet and made a quick bow. “I’m Dill.”

The bird looked him over. Up. Down. Left. Right. When he was done he

turned back to Penelope.

“I’m Penelope,” she said, introducing herself with a curtsy.

“I’m Coo-Coo,” said the bird with a deep nod of his head.

“We’re looking for the Range of Possibilities,” explained Dill. “Do you

know where it is?”

“I . . . do-do,” sang the bird.

“But that’s wonderful!” exclaimed Penelope. “Will you take us to it?”

The Coo-Coo made a slight fluttering motion with his wings. “Coo-coo . . .

if you really want me . . . to-to.” The giant bird crouched next to a large rock,

and Penelope scrambled up and onto his back.

“I hate flying,” groaned Dill. “It always upsets my stomach.”

“It’s the only way,” said Penelope,

coaxing him up.

When they both were settled, the Coo-Coo leapt into the air. Dill made a

sound like a frightened cat and clutched Penelope’s waist. Penelope, however,

laughed with delight as the bird took off. She was reminded of her fantasy to

travel the world by hot air balloon so she could see all the sights. This was

much better!

They flew for miles while the rocky wasteland ran beneath them. Here

and there boulders rose up, dotting the scenery with their jagged forms. Once,

Penelope saw a herd of enormous honey-colored animals picking their way

across the landscape. They looked like deer or antelope, but with much longer

legs and strangely human faces. Their giant antlers were braided together like

elaborate headdresses. When they saw the Coo-Coo, they stopped and bowed

their heads in solemn greeting.

The bird called out, “Coo-coo, coo-coo,” and dipped his wings in salute.

“What were those?” Penelope had never seen such animals.

“Mountain Lopers. It’s a . . . true-true . . . honor to see them. There are

so very . . . few-few . . . left.”

“Did you see them?” said Penelope with a quick glance back at Dill, but his

eyes were clamped shut.

The image of the Mountain Lopers lingered in Penelope’s mind — graceful,

noble, and, somehow, sad. Why were there only a few left? Where had they all gone?

Just then a warm yellow cloud bank rolled across the sky to meet them. It

quickly wrapped them in its soft color and the Mountain Lopers disappeared

from view. Penelope relaxed her grip on the Coo-Coo’s feathered neck and let

her fingers trail beside her. She longed to touch the brilliant streaks of yellow

and gold that billowed around them. The faster they flew, the richer the

yellow grew. Soon the clouds were the color of egg yolk dotted with hints of

pink and fuchsia.

When they burst through, a small chain of colorful mountains appeared

below them. The range spanned from the deepest, darkest blue to the shiniest,

brightest white and everything in between. The foot of each mountain was a single

The Lost Track of Time

The Lost Track of Time